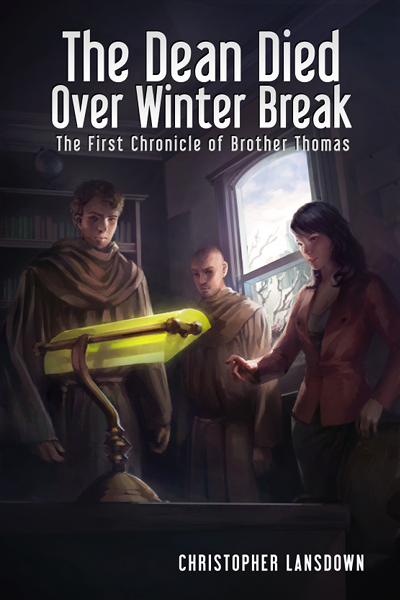

The Dean Died Over Winter Break

Chapter 1

The first that Brother Thomas heard of the death of Jack Floden was in the office of his superior, Brother Wolfgang, in the morning of the twenty-ninth day of December in the year of Our Lord 2014. Brother Thomas had been a friar for seven years, two under permanent vows, in the Franciscan Brothers of Investigation. It was a small, and not very well known, order of consulting detectives.

That not all people are the same was a truth universally acknowledged until the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. Within the Catholic Church in particular this was commonly expressed by the religious orders. They were formed not only for prayer but also for practical purposes, such as running schools and hospitals or providing security to travelers. The order to which Brother Thomas belonged, which was a Franciscan third order regular, was founded in France in 1823. It was formed to do the investigation required to assure bishops that in undertaking collaborations they were not joining themselves to criminal ventures. But the truth is a powerful thing and before long their scope widened as was the range of their geographical reach. In 1894 they were granted the status of a papal order and could go on their own authority outside of their native diocese.

In 1992, the order was asked to come to America, which it did, settling in the Bronx. Two brothers, one French and the other German, were selected to go: Brother Paul who was then 43, and Brother Wolfgang who was 39. By universal consent Brother Wolfgang was made the head of the house. Ordinarily within Franciscan third orders the head of a house is simply the person who takes care of paying bills and calling plumbers, but strange as it may sound to those who've only heard of Saint Francis but never tried to relate to him, Franciscans are intensely practical people. Since consulting detectives require someone to be in charge of meeting clients, vetting them, and deciding whether to take on cases, and since this skill set isn't far from what's needed to run a household, the head of the house was given these responsibilities too.

Brother Wolfgang was now 61. The twenty two years he had spent in America had filed off much of his accent. In his telling it had also given him the silver hair which he kept very neatly trimmed. He was of average height, or rather just slightly under it, and had light blue eyes, almost the color of ice beneath a blue sky. More than one person had been misled by his dignified bearing and careful politeness into missing that wide experience of the world which was visible in the intelligent movement of those blue eyes.

“You wanted to see me, Brother?”

“Yes,” Brother Wolfgang replied. “I've just come back from a meeting with Archbishop Donovan.”

Brother Thomas made no reply. His eyebrows might have raised very slightly.

“Please sit down,” Brother Wolfgang said, gesturing to the two chairs in front of his desk. Brother Thomas picked the less comfortable of the two and sat down on the edge of it, his eagerness well restrained, but still visible to the experienced eyes which looked at him.

“He has asked us to investigate a case which is unusual, even by our standards,” Brother Wolfgang said, when Brother Thomas was as comfortable as he was going to make himself.

“Blackmail?” Brother Thomas asked, taking the clear invitation to guess.

“Murder.”

Brother Thomas raised his eyebrows visibly even to an untrained eye this time.

“Murder! Am I correct in assuming that the murderer is unknown? There seems little reason to bring us in otherwise.”

“You are indeed, correct.”

Brother Wolfgang related the facts directly. On the morning of Monday the twenty second, Jack Floden, dean of the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences of Yalevard University, had been found dead in his office. His body was discovered face down on his desk, the window wide open and snow covering part of the floor. The dean had last been seen alive Friday afternoon, but with the body having been effectively refrigerated, the time of death could not be established. The school had closed early that day because of a snowstorm which started in the afternoon and lasted until Saturday night. What few meetings were scheduled had been canceled and almost nobody had been on campus until the storm let up.

“And that is, indirectly, why we have been consulted,” said Brother Wolfgang.

“On its face, it is a difficult problem,” Brother Thomas agreed.

“I was thinking, rather, of the fact that the universal lack of an alibi casts suspicion upon the entire faculty. Suspicion is a very destructive thing,” said Brother Wolfgang.

“I imagine it might impact alumni donations,” said Brother Thomas.

“It might. How the truth affects the guilty, we of course cannot help. But it is not right that suspicion should harm the innocent.”

Brother Thomas nodded.

“Will you and Brother Francis investigate?”

An indecorous smile very nearly escaped onto Brother Thomas's lips.

“Certainly,” he said.

Brother Wolfgang smiled. His long experience made it unnecessary to complement the younger man on hiding his enthusiasm. The inexperienced need people to know how clever they are. Brother Wolfgang was decades past needing explicit acknowledgement of what he already knew he was. Neither man thought that Brother Thomas was fooling anyone, and nor was he trying to.

“Excellent. Brother Paul and I will of course be available to you if you should need any assistance, though I doubt that you will.”

Brother Thomas nodded.

“Who is it from the University who has called us in?” he asked.

“The president did. He has a friend who is a friend of the Bishop's.”

“Did he say why he wants us?”

“The archbishop did not volunteer a reason, and I thought it impolite to ask what we don't need to know and will in any event find out.”

“Will we need to have a pretext when we investigate?” Brother Thomas asked.

“I don't think so. You will of course need to discuss specifics with President Blendermore yourself before you go there, but I think that the public nature of murder means that this case will require less discretion than do most of our cases. The police will be publicly investigating, in any case. There is little to be gained by hiding the fact that one more investigation is going on as well.”

They spoke for a few minutes about the particulars of how to get to Yalevard and where they would stay, then Brother Thomas left to find Brother Francis.

Brother Francis had been a friar only two years, and was still three years away from taking his permanent vows. He had no doubt he would take them when the opportunity finally came, but neither was he in a rush to take them. In the Franciscan Brothers of Investigation, a brother who has not yet taken permanent vows is partnered with a brother who has, and serves as an apprentice to him. Five to nine years is a lengthy apprenticeship, but consulting detection is a tricky business and there is no substitute for experience. Brother Francis was apprenticed to Brother Thomas, which was an unusual arrangement since Brother Thomas had been independent for only a few months before Brother Francis joined. Brother Wolfgang thought it best, and Brother Paul trusted him.

Brother Francis was in the library reading a book called, “Forty and Going Nowhere,” which attempted to describe the psychology of the mid-life crisis. He looked up when he heard his name spoken.

“We just got a case.”

“Judging by your face, it's an unusual one.”

“Murder.”

Brother Francis raised his eyebrows quite high.

“Wow,” he said. “That is very unusual.”

Brother Thomas nodded.

“I wonder that Wolfgang gave it to us,” said Brother Francis.

“I think that the last time he or Paul investigated a murder was twenty years ago. And besides, he's too much of a realist not to know that I'd have stuck my nose in anyway.”

“Your eye for detail might come in handy,” Brother Francis mused, avoiding comment on Brother Thomas's self-deprecating remark.

Brother Thomas smiled.

“It often does, but who knows how much there will be left to observe after a forensics team has already examined the area. We can't expect them to have left it undisturbed for us.”

“Speaking of which, I wonder how the police will take to us sticking our noses into their case?” Brother Francis mused.

“An excellent question, and while I can't see them welcoming us with open arms, I suspect that it will depend greatly on the person in charge.”

The discussion lasted a few minutes more, mostly comprised of speculation and a few new questions questions without immediate answers. When the topic had been sufficiently discussed, Brother Thomas went to his room to call President Blendermore.

He returned several minutes later, looking on the whole like he had received good news.

“We're to stay at Dr. Blendermore's househe has two guest bedrooms.”

“What is his doctorate in?” Brother Francis asked.

Brother Thomas smiled at the way Brother Francis was certain he had looked up Dr. Blendermore's C.V. while talking to him on the phone.

“He has two, actually. The first is in philosophy. Ten years later he got one in economics.”

Brother Francis nodded.

“Will we need a cover story?”

“Dr. Blendermore sees no need for one. That it would be nice if we didn't talk to the press, was the extent of his concern about what people would think of us being there.”

“When do we leave?”

“I need to do laundry, and we should probably eat something before leaving. Amtrak has service to Yalevard but Brother Wolfgang said that we can take the Sentra since we might need to drive ourselves around once there. I would prefer to keep our options open, so we'll take the car. We might as well leave right after lunch.”

Brother Thomas was known to have to wash his clothes three or even three four times because he would start the wash and then forget about them in the washer, until they'd spent so much time sitting damp that they needed to be re-washed. Brother Francis suspected that in this case Brother Thomas would manage it on the first try.

And indeed, they were packed and on their way to Yalevard by one o'clock.